I’m going to try something a little different here and provide some extracts from an interesting book on history and legends of churches. For those who like to listen, I’m providing an audio version. Please forgive my oddities of accent and pronunciation!

For those who, like me, prefer written form, here is a transcript.

Lore and Legend of the English Church by George S. Tyack

The earliest churches of Christendom were probably oblong in figure, often with a semicircular termination or apse eastwards. But when the faithful became rich enough and had liberty allowed them to build churches openly and after such designs as they wished, different ground plans were adopted according to fancy or local custom.

The Apostolical Constitutions, a work dating probably from the fourth or fifth century, orders that the building be “long with its head to the east, with its vestries on both sides of the east end, and so it will be like a ship. In the middle, let the bishop's throne be placed, and on each side of him let the priesthood sit down.”

Yet the churches erected at Antioch by the Emperor Constantine and at Nazianzum by the father of St. Gregory were octagonal. The church of the Holy Sepulchre, founded by the same emperor, was circular. And at an early date, cruciform churches were built in some places, as in the examples of the one dedicated to the Holy Apostles at Constantinople and one built by St. Simon Stylites and described by Evagrius.

In England, it is very evident that the earliest churches were humble structures, suitable to the means and the taste of a people just emerging from barbarism. A simple parallelogram would doubtless be the form commonly chosen, with walls of timber and roof of thatch.

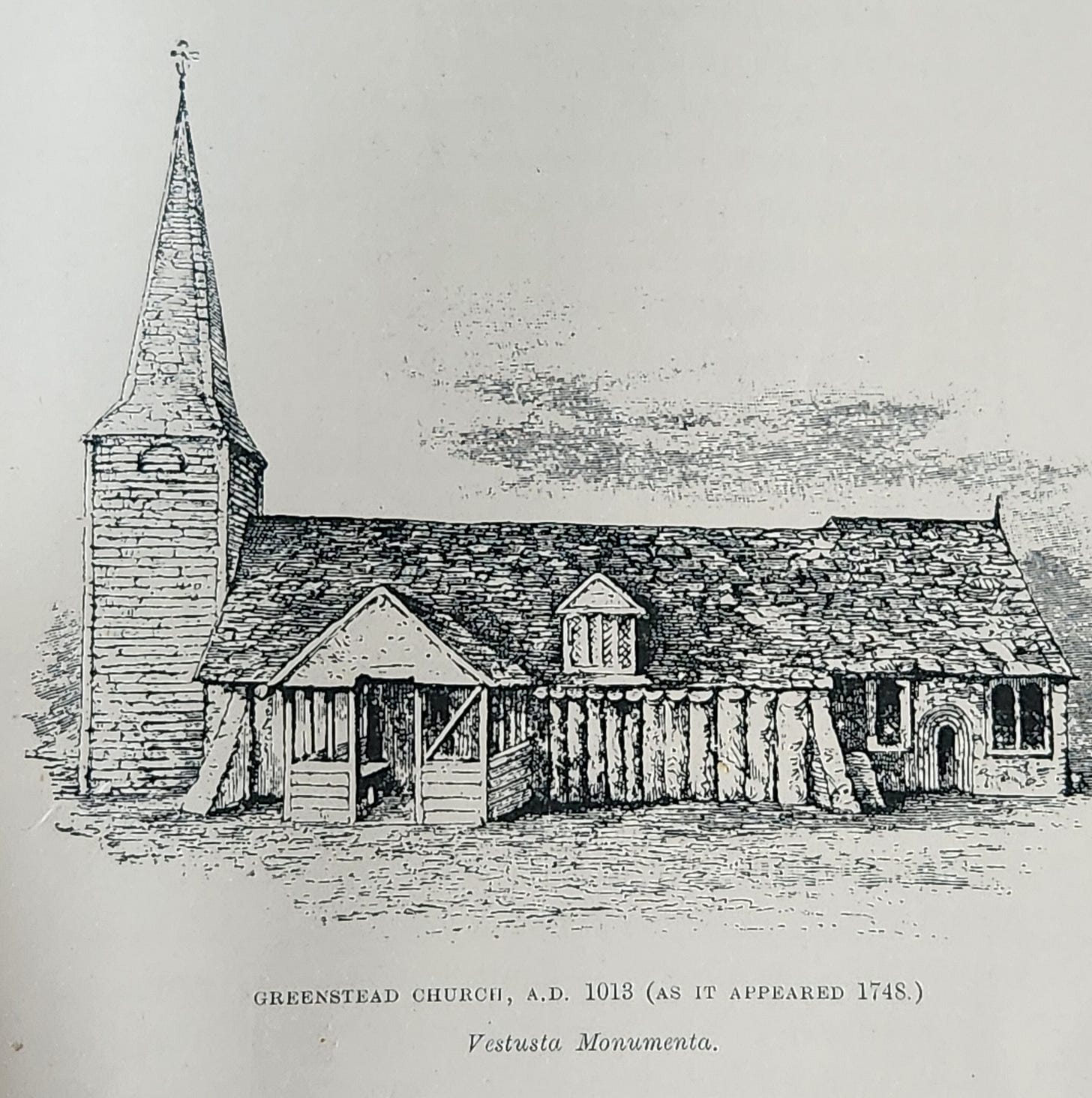

In the quaint little church at Greenstead, we have an example of such a building which, so far as the major part of it is concerned, has probably weathered the storms of well-nigh nine centuries. It is only fair, however, to admit that in this case the structure was probably only meant originally as a chapel.

The church at Greenstead, from George S. Tyack’s book.

There is ample evidence, however, of ecclesiastical erections of greater importance, having been formed in much the same primitive fashion. The great abbey of Croyland was, as Engulfus tells us, built originally of logs and planks, and such also was Malmesbury Abbey in the days of King Edgar and Glastonbury in those of Cnut. Finan, the successor of St Aidan in the Sea of Lindisfarne, built himself a church on the island of hewn oak covered with reeds, and it was the strangeness of the site of a church built of stone by St Ninian that gained its name for Whitehouse in Galloway.

Durham still had a wooden chapel of St Aldhelm, down to 998, and at Bury St Edmunds, one survived as late as 1303. St Edward the Confessor is reputed to have introduced cruciform churches into England in the erection of Westminster Abbey, and that ground plan has since been adopted for almost all our large churches and for many of the smaller ones.

The legend, which has already been noticed to the effect that four cows lying crosswise both indicated the site and suggested the form of the church at Alfreston, seems to point to a time when the cruciform design was not recognised as in any way a common one in the country.

A form more curious and less usual is the circular of which several examples are to be found in England. Allusion has already been made to the round Church, which was originally built over the alleged site of the Holy Sepulchre, and it is the memory of this venerable building which is perpetuated in our churches of a similar design.

The Knights Templars, in the preceptories which they erected throughout Europe, preserved the form of that sacred place which they had been specially enrolled to defend. and it is to them that we owe our round churches.

In the Temple Church in London, we have the chief ecclesiastical edifice of the Knights Templars in Britain, and the most beautiful and perfect memorial of the Order now in existence. The rotunda was erected about the year 1185, the rest being added during the following century.

St Sepulchre's, Cambridge, is the oldest of the group of buildings of this type still surviving in England. The rotunda here is of Norman architecture and to this a chancel was added about 1313.

Northampton has another round church also dedicated in the same as St Sepulchre. The characteristic portion was built in the end of the 11th century and to this large additions were made at later times.

The only other example and the smallest is at Little Maplestead in Essex. This parish was granted to the Templars by the Lady Giuliana de Borgo in 1186, and the buildings were probably commenced soon afterwards. The rotunda measures only 30 feet in diameter, and from this runs a chancel another 30 feet in length but only 15 in width. At the commencement of this century, this interesting little church stood roofless and well-nigh ruined, It has since been repaired, but necessarily at the cost of much of the original work.

A yet smaller round church stood at one time on the heights of Dover, its diameter being but 25 feet and its chancel measuring 27 by 14. Only the foundations now remain of this ancient edifice in which, tradition says, took place the conference between King John and the legate Pandulph.

The custom of placing the chancel and altar at the east end of the church, though ancient and everywhere common, has scarcely anywhere been preserved so scrupulously as in England.

Stephen, Bishop of Tournai, in a letter to Lucius III, Pope from 1181 to 1185, speaks of this orientation as a peculiarity at St. Bernard's, Paris. and there are churches in Italy where the altar stands at the west end.

An exception to what was certainly the primitive rule in England is exceedingly rare among churches of any antiquity.

Though the orientation of our churches has been for the most part preserved, it is not an uncommon thing for them to vary several points from due east and west. There is a theory that the exact degree of inclination was determined by marking the spot on the horizon at which the sun rose on the feast day of the saint in whose honour the church was to be dedicated. The theory is ingenious and possibly has an amount of truth in it with regard to some instances, but it can hardly be counted as more than a theory.

There are many curious facts and stories in connection with the raising of funds for building churches in medieval times. In a very large number of instances, our parish churches were built at the sole charge of some wealthy and pious lord of the manor, or by some great monastic house.

Even in such vast structures as our cathedrals, much was also done voluntarily, the monks being their own architects, sculptors and masons in many cases.

But in bygone times, as well as in modern ones, it was not always that the needful funds came readily to the hands of those who desired to build. Any place which possessed an attraction for pilgrims was glad to turn that fact to account for the improvement of its church. It was the offerings at the Shrine of St Wilfrid which assisted in the completion of the collegiate church, now the Cathedral of Ripon and the east window at Rochester is the fruit of the alms box beside the Shrine of St William of Perth.

The west front of Ripon Cathedral

And these are but types of what went on throughout the country in those early days.

Again, it would frequently happen that a guild or confraternity would undertake to build, or it may be to keep in repair, some portion of a church.

Ludlow Church has an iron arrow affixed to the roof of the North Chancel Isle, marking the fact that the portion of the church there is the Fletcher's Chancel, or Chantry Chapel of the Guild of Arrowsmiths. It is surely reasonable to suppose that the chapel thus marked with their emblem was built wholly or largely at their expense. The local legend used to be that Robin Hood, standing on one of the tumuli hard by, which is still called by his name, aimed with his bow and arrow at the weathercock on the steeple but this arrow, missing the mark, stuck in the roof where it is now to be seen. Even such a marksman as bold Robin Hood might be pardoned for inaccuracy of aim had he to shoot with iron arrows.

In the 14th century, the young men of Yarmouth designed to build an isle, the Bachelor's Isle, in addition to those already existing in their parish church. But the outbreak of the Black Death put a stop to their work.

The inscription, Young Men and Maidens, which is cut twice on the fine tower of All Saints Church Derby, is supposed to commemorate the fact that the bachelors and maidens of the town made themselves responsible for its erection up to that point. Some carving on the west front of Bath Abbey is commemorative of a vision which led to the restoration of that building. Oliver King said, On his translation in 1495, from the Sea of Exeter to that of Bath and Wells, found the abbey in the latter city an absolute ruin.

While meditating one night over this grievous state of things, he saw a vision like that of Jacob of old, a ladder up which the holy angels passed, while at the top glowed the presence of the Blessed Trinity. Beside the ladder, a fair olive tree spread its branches in support of a royal crown. and a voice seemed to say in his ear, let an olive establish the crown and a king restore the church. Encouraged by this divine intimation, he set manfully to work to rebuild the abbey in the year 1500, and although he did not live to see it completed, he was able to do much, and on the western front he carved the ladder of his visions.

Another Somersetshire story of church building comes from Monk Silver and here too it reads itself around some carving in the church. In the heads of the windows in the South Isle are cut the figures of a hammer, a nail, a pair of pincers and a horseshoe, whereby the villagers say hangs this tale.

Long years ago a worthy blacksmith in the place sent to Bristol for a hundred weight of iron and in due time received a sack filled with metal. But when he opened it, it proved to be full of glistening gold. In thankfulness for this sudden wealth, he built this south aisle to his parish church and commemorated in the carving the fact that it was a blacksmith's gift.

The legend does not condescend to tell us what steps, if any, the worthy man took to find the true owner of the wealth.

Finding is keeping, usually, in folklore tales.

Share this post