The Naves of our churches were anciently adorned with permanent decorations far more frequently than is now the case, paintings and statues at once serving to remove the bareness of the walls and to instruct the worshippers. Over the chancel arch was usually a doom or emblematic painting of the Last Judgement, of which traces still remain in several English churches. Other paintings often covered the walls and made them as full of teaching as we have at least agreed that our windows may be. Statues also stood in their niches against the pillars or besides the lesser altars. The patron saint of England, St George, was represented in many churches in a splendid fashion, an equestrian figure richly decorated being erected in his honour.

Sinners being swallowed up in the mouth of hell, at Pickering church (15th century)

The Puritan Hollingworth, writing of Manchester in 1656, says, “In the chappell where morning sermons were wont to be preached, called St George’s chappell, was the statue of St George on horseback, hanged up. His horse was lately in the sadler's shop. The statues of the Virgin Mary and St. Dyonise, the patron saints, were upon the highest pillars next to the choir.1 Unto them men did usually bow at their coming in the church.”

St George at Pickering, 15th century

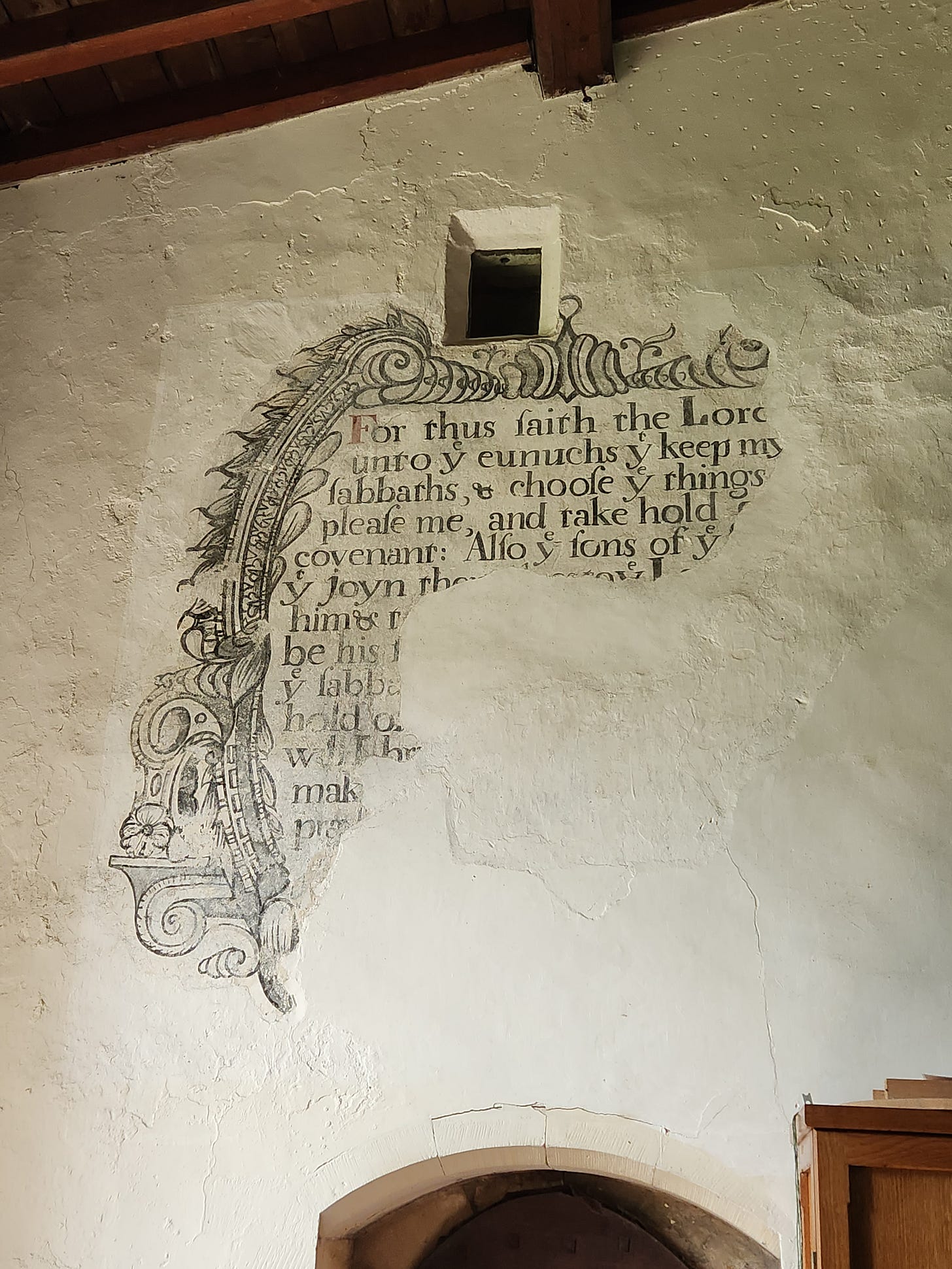

The Reformers had a most illogical dislike to painting and sculpture, admitting, as Hooper does in his “Declaration of Christ and his Office,” that “the art of graving and painting is the gift of God,” they, nevertheless, would altogether exclude its existence from the house of God. Even painted windows were to be destroyed, and “if they will have anything painted”, writes Hooper again to the clergy of Gloucester, “let it be either branches, flowers, or posies, (mottos) taken out of Holy Scripture”; he goes on to order the defacement of all “images painted upon any of the walls.” Thenceforth, therefore, the only decoration to be suffered was branches of unmeaning foliage, or texts unreadable by the larger part of a country congregation at that time. Happily, these narrow views have no authority beyond that of the individuals who expressed them, although the 89th Canon of 1604 desires that chosen sentences be written upon the walls of the churches and chapels in places convenient. But the destruction which was commenced under such leadership was carried out with ruthless logic to its natural conclusions by the Puritans of the following century. Something has been done in recent years to repair the loss of the past centuries, but much yet remains to be done before the interiors of our churches will bear comparison with the artistic decoration that we, at any rate, aim at in our homes.

A remnant of a motto painting, most likely 17th century, at St Agatha, Easby, Yorkshire

Not many of our churches have paintings by well-known artists though there are exceptions. The celebrated picture of Christ as the “Light of the world” by Holman Hunt is now in Keble College Chapel; and in the parish church of Chinnor, Oxfordshire, are effigies of the eleven faithful apostles, the four evangelists, and of our blessed Lord, said to be the work of Sir James Thornhill. The same artist executed paintings within the Dome and St Pauls, which have now been replaced by the more effective mosaics. Other cases might be quoted, but we are far behind the Continent in this respect, where the masterpieces of the greatest artists have been placed for the most part in the churches, and not in mere picture galleries, public or private.

The more temporary adornment of churches with flowers and foliage has a very high antiquity. Paulinus, Bishop of Nola, describing the preparation for keeping a festival, exclaims, “Strew ye the floor with flowers, with boughs the threshold weave.” St. Jerome tells us that his friend Nepotian “made flowers of various kinds, the leaves of trees and the branches of the vine contribute to the beauty and decoration of the church”; and he adds words which well express the principle on which such things and others, which a sour Puritanism is wont to sneer at, are admirable. “These things, he says, are in themselves but trifling; but a pious mind, devoted to Christ, is careful of small things, as well as great, and leaves undone nothing that belongs even to the lowliest office in the church.”

Christmastime has long been the great occasion of decoration in English churches, and the usage of holly, ivy and box at that season has lasted in an unbroken tradition through all the days of carelessness and neglect. Of all the foliage available at that cold time, mistletoe alone seems by universal agreement to be excluded from the church. It was the sacred plant of the Druids, which may have made the Church cautious of using it, but it was also the plant which supplied the fatal shaft which slew Baldr the Beautiful, and it may therefore mean that our Saxon forefathers so far clung to their ancestral myths that they would not use the death symbol of Baldr at the birth of the White Christ. The secular frivolities connected with the mistletoe have no doubt had something to do with keeping it out of church in more recent times. It is said that there is only one instance of mistletoe being introduced in the carving of an English church and that is on a tomb in Bristol Cathedral.

The Christmas decorations must be taken down before Candlemas Day and if but a single leaf or berry be left in a pew, some one of those who usually occupy that seat will die before another Yuletide; such at least is the belief of many, and people have been known to send their own servants to the church to sweep out their pews most carefully on Candlemas Eve.

Easter is now becoming almost as generally marked by its decorations as Christmas, and no season provides flowers more effective for the purpose than a fine spring. Whitsuntide has scarcely yet been accorded equal honours, yet it was specially regarded by our forefathers. It used to be customary to deck the churches in Shropshire with boughs of birch at the feast of Pentecost, and the same method of garnishing was in vogue in Staffordshire, if we may judge by some items in the Bilston accounts. In 1691 we read, “for dressing the chapel with birch, 6d.” In 1697, “for birch to dress the chapel at Whitsuntide, 6d.” And again in 1702, “for dressing the chapel and to Anne Knowles for birch and a rose, 10d.” The same tree is a favourite for a Whitsuntide decoration in Germany.

The festival of St. Barnabas the Apostle, June 11th, was of old observed with special devotion in England, perhaps owing to its proximity to Midsummer Day. The churches were dressed for the anniversary with roses, lavender, and woodruff.

A singular custom existed at Ripon on Christmas Day at one time. The boys of the choir came to church provided with baskets full of rosy apples, in each of which was stuck a sprig of rosemary or box. These were carried round and offered to the members of the congregation, who were expected to give some little gratuity, varying usually from twopence to sixpence in return.

Before leaving our consideration of the nave with its uses and abuses, its disfigurements and decorations, one curious form of adornment that has been accidentally introduced into several churches should be mentioned, and that is the existence of trees growing and flourishing within the building. At Ross Church, in the pew rendered memorable by its regular use by John Kyle, Pope's Man of Ross, two trees may be seen growing. There are other examples which, though not standing in the naves of churches, it will be convenient to mention here. A chestnut tree grows from the tomb of Sir Edmund Wilde in the chancel of Kempsey Church near Worcester. Some years ago a lad sitting in the chancel was discovered eating chestnuts, and one in his hand was snatched from him and flung behind this tomb. There it has taken root and grown in spite of efforts to dislodge it. Outside, at least two churches, trees have sprung out of the walls. At Castle Morton, near Tewksbury, is one growing from the side of the spire, and at Whaplode, in Lincolnshire, is a birch tree on the tower.

Have you seen my new publication - Shepherd’s Prayer? Available now via Amazon around the world, see here for more details.

I find this passage very interesting; though most pillars are now stripped of plaster and paint, the few traces that remain often indicate the key saint of the church. In the church of St John the Baptist in Chester, a superb image of St John himself is still preserved on the left pillar, as you look towards the chancel. It’s also interesting that even in the 17th century, the custom of bowing to images of the saints is preserved.

Share this post