The gifts made at the shrines of famous saints within the cathedrals and abbeys of the country were often remarkable both in number and in value. The offerings in money at the Shrine of St. Hugh at Lincoln reached in 1365 the sum of £37 14s 8d, a large amount when we remember the difference in the purchasing power of money between the fourteenth century and our own. But many gifts were made in kind. The head of St Hugh, placed in a separate shrine had a mitre of silver, and about the reliquary which contained it were rings set with precious stones, old gold coins, branches of coral and other valuable offerings from the devout pilgrims. At Canterbury, the shrine of St. Thomas is described as “blazing with gold and jewels and embossed with innumerable pearls and jewels and rings.”

The spot where St Thomas’s second, magnificent shrine, once stood.

Henry VIII, on visiting the shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham, gave a massive chain of gold for the adornment of the statue. And Erasmus tells us that the shrine looked like “the mansion of the saints, so much did it glitter with gold, jewels and silver on all sides.” These are but samples of the lavish way in which medieval Englishmen devoted their money and valuable possessions to the enrichment and adornment of the churches. So great was the accumulated wealth in many abbeys that a special watching chamber was erected within the church, whence continual watch could be kept over the treasures of the place by a succession of monks.

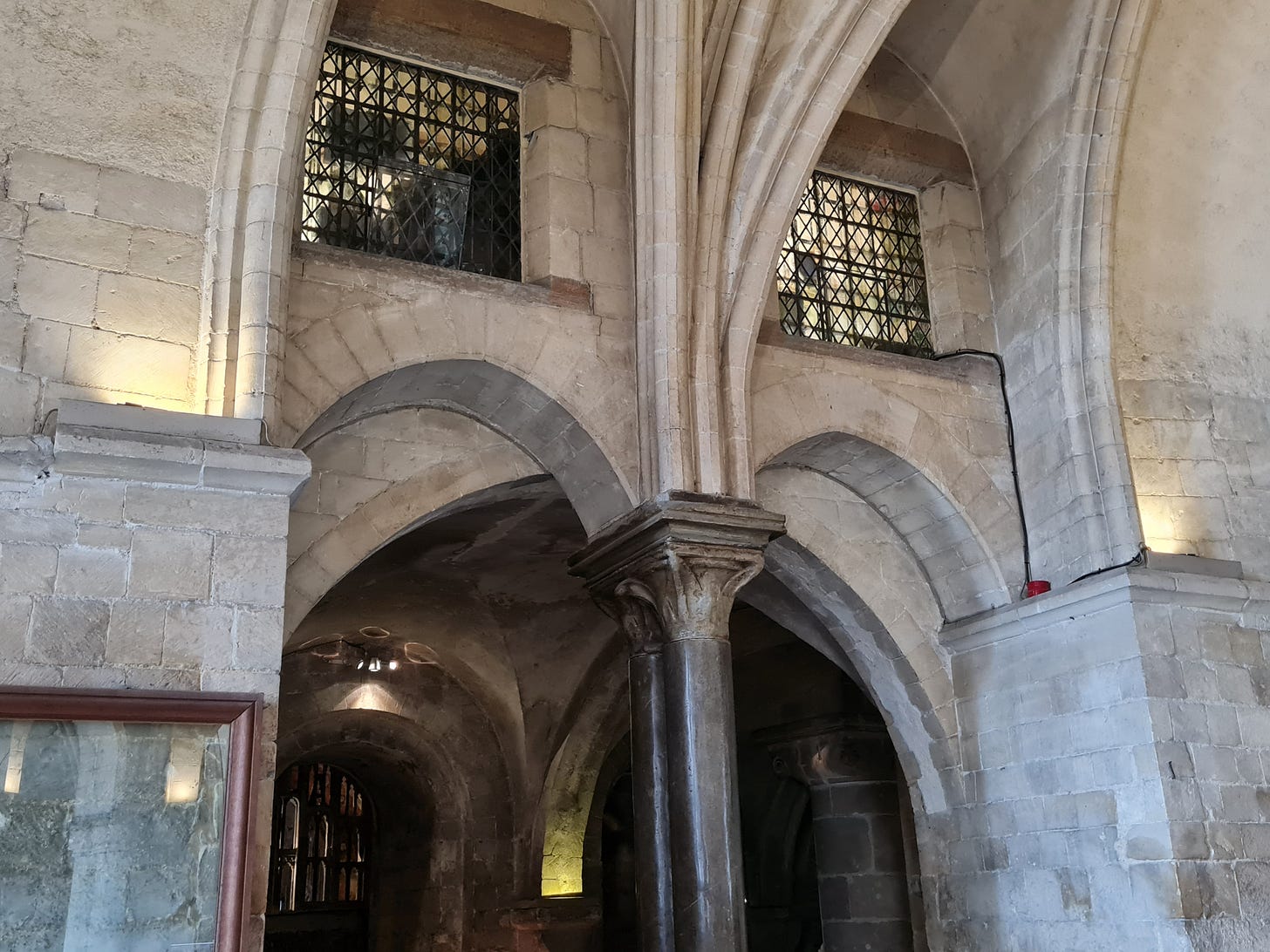

The watching chamber above St Thomas of Canterbury’s original shrine in the crypt.

With all their caution, however, the monks were not always able to defend the shrines from the depredations of villains who “feared not God nor regarded man;” and then occasionally the saints put forth their wondrous powers and themselves avenged the violation of their resting places. Such a miracle once happened at Durham, as the chronicler Simeon tells us. It was in the days when Egelwine ruled the see (1056 to 1071), that a noble pilgrim to the sacred relics of St Cuthbert brought in his retinue a varlet whose greedy heart wrecked more of gold than of godliness. The mass of money left by recent visitors at the shrine and still lying in shining heaps upon it set this man's eyes a-twinkling, and he longed to slip into his leathern pouch some of the silver pieces. Presently he drew near amid the throng and saw the people all in turn stoop and kiss the cold marble beneath which lay the remains of so much saintliness. The Tempter, ever at the elbow of the children of men, even when they stand between the altar of God and the tombs of the blessed, whispered in his ear to do likewise and at the same time to help himself. Right humbly did the hypocrite bow him at the shrine, and long and fervently did he press his wicked lips to the marble; but it was nothing but a Judas kiss which he gave, for money, and not for devotion. Rising up, he turned to move away, with four or five silver pennies, reft from the blessed St. Cuthbert in his mouth, and no one had noted aught of his evil deed. But presently that ill-gotten store of coins began to glow within his mouth, as if they were heating in a furnace; fain would the wretch have slipped them into his wallet, nay gladly would he even have spat them out upon the floor in the sight of all men for they grew ever hotter and the torment was intolerable but his jaws claved to each other as if they had been locked; and strive as he would he could not open them. Thus was he driven to rush madly through the throng of wonder-stricken folk, waving on high his hands which clutched and snatched at the air, and groaning like the ox that goes to the slaughter, with wild inarticulate bellowings. At last he betakes him again to the shrine, and flinging him down beside it, asks in his heart for the pardon of his crime, and for the tender pity of the blessed St. Cuthbert; and lo! his lips open, and forth therefrom roll out the coins; and he is at once whole and well again. So mightily, if the chroniclers say sooth, can the saints defend their honour and the charitable offerings of their devout clients.

St Cuthbert’s grave, where his shrine once stood.

In 1364 the casket containing the head of St Hugh of Lincoln was stolen with its venerated contents. In this case also the thieves gained no advantage by the sacrilegious robbery, for they were discovered convicted and hanged.

The offerings at shrines and the thefts from them have been terminated among us, not only by the suppression of pilgrimages, but by the wholesale ruin of the shrines themselves and the scattering of their precious contents. In face of the spirit of destruction that loose at the time of the Reformation, very few of the relics which the English church possessed were left to her. At this distance of time, we can afford to forgive those who sacrilegiously bore away the golds and jewels of reliquaries and turned them to their own base purposes. But the ruthless dismemberment of the bodies of the saintly dead and the scattering of their bones upon the dunghills was an act that could only be perpetrated by godless ruffians, and one for which no pleas of former superstitious usage, no claim of good intentions, can be admitted for one moment as excuses or extenuations.

Bede’s tomb in Durham Cathedral.

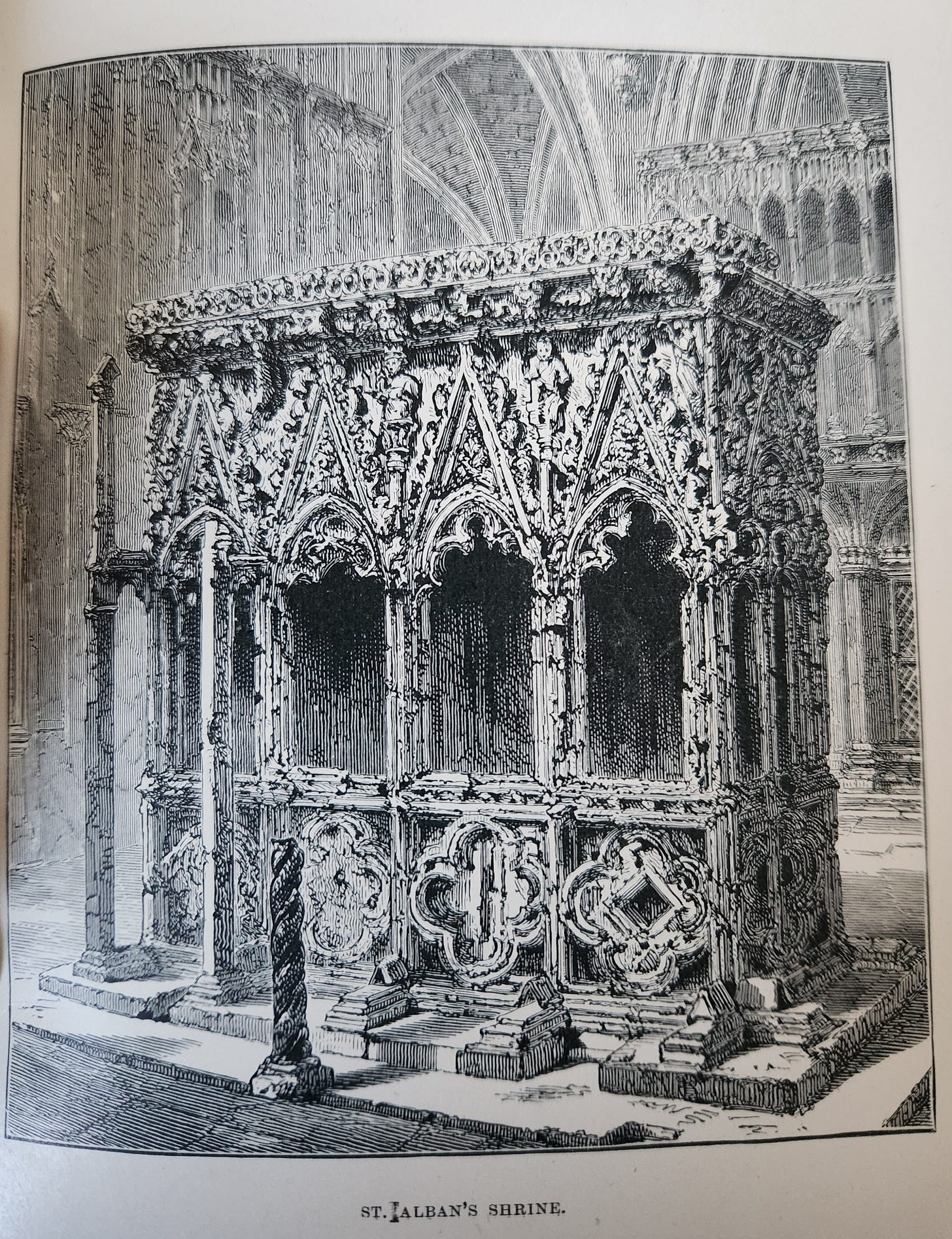

Westminster still has the relics of St Edward the Confessor and Durham claims to possess those of St Cuthbert though the fact is disputed.1 His shrine and that of the Venerable Bede were demolished; the coffins were smashed open with a hammer and an attempt was actually made to tear in pieces the uncorrupted body of the former! Finally, the relics were locked up in the vestry to await further orders, and at a subsequent time were re-interred. It was long thought that Lincoln still had the body of St Hugh, and a tomb was erected in the 17th century over his supposed resting place, but recently it has been found that no remains are there. At Salisbury are the relics of St. Osmond, at Canterbury those of St. Alphege, and at Ripon, probably, those of St. Wilfred.2 The Shrine of St. Thomas of Canterbury and its famous contents could, of course, look for no mercy from King Henry VIII, and certainly got none; for they recalled the life of an archbishop who had successfully resisted a king. The Shrine of St. Alban, recently reconstructed from the fragments variously discovered during the restoration of the cathedral of St. Albans, only for a short time contained the genuine relics of the English proto-martyr. During the Danish incursions, the monks, fearing for the safety of their treasures, exhumed the body and translated it to Ely, and in quieter days the monks of Ely refused to return it. On this the brethren at St. Albans discovered another body and declared that the Ely relics were not genuine, but that the real remains of St. Alban had been hidden, not translated. Whose were the bones dispersed at the Reformation, it is therefore impossible to say. The shrine is now, of course, a mere cenotaph.3

From Lore & Legend of the English Church.

Doubtless there are, hidden away by pious hands, in many churches up and down the country, the once honoured relics of saints of old. But their hiding places have been forgotten. Within quite recent years the body of St. Eanswythe, the abbess and patroness of Folkestone, has been discovered within a leaden casket in the parish church of the town, and it may be that yet others may be found elsewhere in the course of time.4 Within the crypt of St. Lawrence's church at Chorley lie the remains of St. Lawrence. These were brought from Normandy in 1442 by Sir Roland Standish and placed by him where they still lie.5 Though no one can suppose them to be the genuine relics of the Roman deacon of the third century, they are probably those of one of the less known saints of the same name, of whom there are several. The dismembered body of the best-known St. Lawrence, with fragments of the gridiron on which he suffered, of his dalmatic and other relics of him, are preserved in several of the churches in the city of Rome.

This is where the book ends. I hope you have found it interesting. At present I have no idea what I am going to replace it with for my Monday posts, but I’m sure I will find something!

Have you seen my new publication - a translation of Shepherd’s Prayer by St Aelred of Rievaulx? Available now via Amazon around the world, the isbn is: 979-8344184814.

Since this was written, further analysis indicates that St Cuthbert’s remains are indeed still there, along with some others. Like wise Bede is still in his tomb.

St Wilfrid is not at Ripon, his relics were moved and lost.

Recently a relic of St Alban was returned to the Cathedral, to be placed in a new shrine.

Relics of St Chad (patron of Lichfield) were hidden by English Catholics for centuries and recently restored to the cathedral, I believe. I will be visiting later this month so will update you on this!

I have been unable to confirm this.

Share this post