We have now passed the Gloria and move on to the prayers and readings. If this is the first time you are reading this series of posts, notes are at the end.

And when thou hast this all done,

kneel down on thy knees sone [some].

If thou of letter can,

to the priest hearken than [then].

His office, prayer and pistille [epistle],

and answer thereto with good will,

or on a book thyself it read.

If thou can naught read ne say

thy pater noster rehearse alway

till the deacon or the priest the gospel read,

stand up then and take good heed;

for then the priest flits his book

north to that other altar nook,

and makes a cross upon the letter

with his thumb, he speeds the better,

and sithen [afterwards] another on his face.

At the beginning tent [intent] thou take,

a large cross on thee thou make.

Stand and say on this manere [manner]

as thou may see written here.

In the name of father, and son, and the holy ghost,

and steadfast God of might-es most;

be God’s word welcome to me,

joy and loving, Lord, to thee.

When it is read, speak thou naught,

but think on him that dear thee bought,

saying thus in thy mind,

as thou shalt after written find.

Jesu, mine, grant me grace,

and of amendment might and space,

thy word to keep and do thy will,

the good to choose and leave the ill,

and that it so may be,

good Jesu, grant it me. Amen.

Rehearse this oft in thy thought,

till the gospel be done forget it naught;

somewhere beside, when it is done,

thou make a cross, and kiss it sone [some].

There’s quite a lot to unpack in this post. A good place to start is to describe which bits of the Mass are covered in this section, which comes after the Gloria is said or sung. The sequence is as follows (all said in Latin of course):

Priest kisses the altar

Priest: “The Lord be with you”

Server/People: “And with your spirit”

Priest: “Let us pray”

Priest reads the Collect (prayer) of the day, perhaps followed by another collect

People: “Amen”

Priest/Deacon reads the Epistle

Priest reads the Gradual and Alleluia (made from verses of the Psalms)

Priest/Deacon: “The Lord be with you”

Server/People: “And with your spirit”

Server/People “Glory to you Lord”

Priest/Deacon reads the Gospel

Server/People: “Praise to you O Christ”

This section starts with instructing people to kneel, so it seems they would have stood during the Gloria. This is slightly different from the Low Mass today, where people mostly kneel from the beginning up to the Epistle, at which they sit. Of course, at the time this was written, there were no pews in churches so people had to stand or kneel.

It’s worth noting that the congregation are instructed to “answer thereto with good will” - this is presumably referring to the responses written above.

What is the priest’s “office”? We might think it refers to the Divine Office, but the word has another meaning, also used by St Benedict occasionally. In the context of the Mass, it means saying the parts and doing the things proper to him - so reading the introits, prayers and kissing the altar, for example. Only the priest can do these things.

“If thou of letter can” - if you can read and perhaps understand some Latin, you should follow what is said. I particularly like the word “pistille” for epistle! There is an assumption here that some attending would have had texts with them. From the late 14th century onwards, epistles and gospels for the Sundays would be given in primers, which were originally handwritten books used by the middle and upper classes. With the invention of the printing press, pamphlets in English became cheap and easy to produce.

For those who couldn’t read, they are instructed to say their pater noster. This phrase could mean simply saying that prayer but equally it could refer to prayer beads which, before the rosary supplanted it, were referred to as a “pater noster”. The purpose here is for people to keep their minds on the Mass and not allow their thoughts to wander if they did not know what the priest was saying.

A bedesman with his paternoster beads at Godshill, Isle of Wight. Apologies for the poor quality phot - this was very difficult to snap.

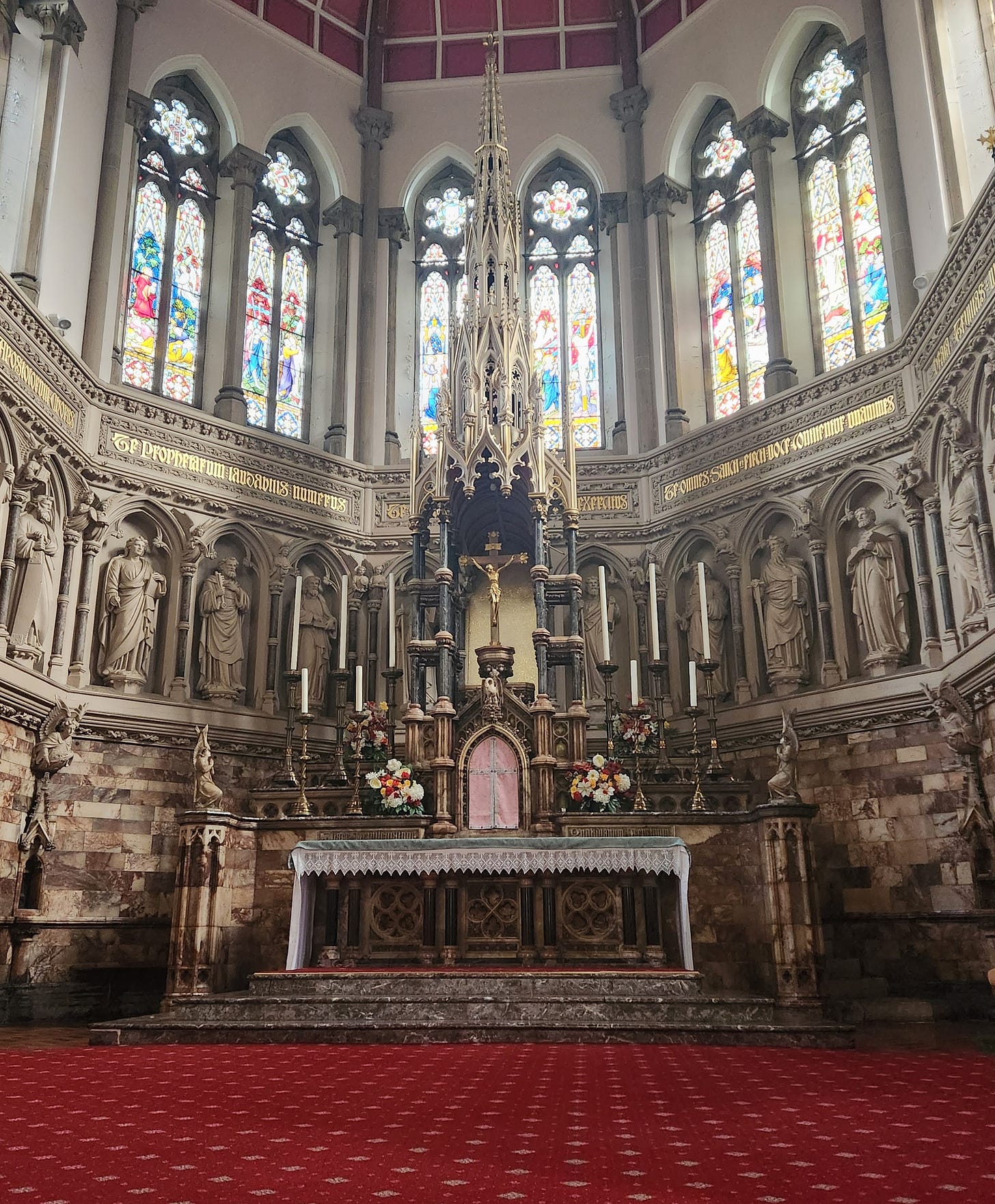

In the traditional Mass, the Epistle is read from the south side of the altar (the right end); the server then moves the book from the south to the north side (the left), where the Gospel is read. If there is a deacon present, he reads the gospel - we should remember that in the medieval period, each parish would have multiple clerics; priests, deacons, sub-deacons and others in the minor orders preparatory to priesthood.

The priest makes a cross on the gospel page with his thumb, still done today though as the priest faces the people in the new Mass, it may not be obvious to the congregation. The congregations then signs themselves with the cross, but of course now we do it slightly differently, makin crosses on our foreheads, lips and heart, which I think actually reflects the small prayer in this text.

The Gospel is read in Latin, which some of the people present would not understand, so the text instructs people to be silent and think about Jesus. It gives a prayer to assist them.

What’s interesting to me here is the instruction “rehearse this oft in thy thought”; often people say that medieval Christians did not practise mental prayer but only the vocal kind. This text says differently.

At the end of the Gospel reading there is an instruction which may seem strange to us - “somewhere beside, when it is done, there make a cross, and kiss it sone”. The commentary in the book explains this as an old practice which had largely disappeared by the 19th century, hanging on only in rural places in countries such as Ireland. If they had a book with the Gospel text in it, they would make a cross on it and kiss it. If they had no book, they would make a cross with their thumb (just like at the beginning) and the kiss their thumbnail, hand or finger. A sign of devotion and commitment to putting the gospel into practice.

The text doesn’t talk about this but we know from documentary sources that if there was a homily, the priest would read the Epistle and Gospel in English first, as is usually done in Latin Mass churches to this day. The homily would of course be in English too, so religious instruction would be given every Sunday.

I think my favourite part of this bit of the text is the prayer:

Jesu, mine, grant me grace, and of amendment might and space, thy word to keep and do thy will, the good to choose and leave the ill, and that it so may be, good Jesu, grant it me. Amen.

Amen indeed.

This is an excerpt from The Lay Folks Mass Book, a verse poem from the 14th/15th century, originally written in Middle English.

Each Sunday I post a short excerpt, transcribed into modern English for ease of reading, and harmonised from the 4 surviving versions which are in different dialects and with some variations in text.

Notes on the transcription: like German, the letter “e” on the end of words is often pronounced. In general, modern English has dropped all these so in transcribing it I have generally followed modern English which means that in most cases the rhyme and meter work. But occasionally, I have put letters in square brackets where required for the verse, or sometimes separated the endings with a hyphen to indicate that they should be pronounced as a separate syllable.

Most of the words have a modern English equivalent which is very similar, but where that doesn’t happen I have put the meaning in [ ].

One important word: the term for Mass in middle English is Messe, with the “e” pronounced, as in German. I have generally written it as Mess for the sake of the rhyming.

The text used is the one published by Thomas Frederick Simmons in 1879 and reprinted in 1968.

Thank you for doing this series. It's inspiring to read about the faith and devotion of Catholics from centuries ago. It's also a shame that certain practices, like reading the Gospel from the south side of the altar, is completely gone in the new Mass. This ancient symbolism is wholly foreign to us today. Thankfully, the TLM still preserves the tradition.

I love the photo of the Bedesman! And also the rubric for what to do if there was no book for the Gospel. That even the spoken word from memory is holy and receives a cross in the air.