St Bees Priory

A blast from my past

As I am going through my old photos and moving them to new storage locations, I intend to do some posts on some of the ancient churches I haven’t covered. these posts will be entirely random, so beware!

First up, St Bees. This is now a small town on the west coast of northern England. In ancient times it was clearly on the sea highway and a prime place for the Irish missionaries to land, but these days it is a little out of the way and a pleasant place to stay, which I did in 2022.

The old priory sits out of the worst of the wind in the lee of the monumental St Bees head. The name “Bee” is a corruption of Bega; St Bega was in Irish saint around the 7th century who founded a nunnery here. She was said to be an Irish princess who fled here to escape a forced marriage and the principal relic held here was St Bee’s bracelet. The traces of that early monastic foundation are gone, or rather most likely underground, but the church was developed time and time again over the centuries. A Benedictine priory was placed here in the 12th century and much of the ancient church dates from that period.

Parts of the church collapsed or were repurposed over the years; in this photo you can see the arches of a south aisle with two chapels; this lay to the south of the chancel. To the right of the tower you can see end of the current church; the chancel has been shortened a lot after the dissolution of the monastery.

This is the main door, at the west end of the church. It is a typical Norman shape, with multiple chevroned arches, and carved capitals atop pillars, most of which have been robbed out. It is 12th century and you can see the weathering of the soft sandstone very clearly.

Opposite this door is this stone, placed above two supporting walls. This is likely to be 10th or 11th century in date so older than the present church.

Nearby is this stone, a type which is certainly pre-12th century and could go back much further.

When new, the arch and decoration would have been covered in limewash and painted. In fact, the whole church would have been painted; most of the erosion we see in ancient churches today is down to the neglect of the limewash which once protected them - failure to replace the plaster ultimately damages the fabric of the church.

Above the door are three windows which most likely started out as round-headed Norman windows in the 12th century but look to have been remodelled according to later fashions.

This is what they look like on the inside.

This is the inside. If you’re familiar with the normal proportions of a church you can see how short the modern chancel is, with a largely blank wall at the end. It’s highly unusual and actually makes the church very dark. The pillars are a mix of round and octagonal ones, with pointed arches. The one on the extreme left is a bit odd. It has a cockleshell above the pillar capital and is thought to have represented something - the end point of a pilgrimage perhaps - the aisles most likely contained chapels and it may be that St Bega’s chapel was there. The round pillars on the left and right may possibly be a physical representation of the crucifixion; the cross standing between the two thieves, represented by the octagonal columns. I wasn’t aware of this practice when I originally visited the church but there has to be some reason why there are two round pillars among the octagonal ones.

Some of the pillars have decorated capitals - this looks to be 12th century.

This one is a little later than the first, with lovely stiff leaf carving.

A cross base from the 10th or 11th century stands in the church, along with some old gravestones.

This one is likely to be the gravestone of a priest, given the iconography here - chalice and blessed sacrament.

This one is fascinating - very long, which is why I didn’t manage to get it all in the shot. Late 12th century, featuring a bowman and a sword and so we assume that this person was an accomplished soldier. At the top, the dangly items in the middle are 12th century stirrups. The circular objects wither side of the central cross are, I suspect, representations of a horses harness, which fits neatly with the theme here. So he may have been a knight or an armed servant of the priory of some importance to them.

This one is of a woman, most likely 13th century, she was connected to an important local family and died young.

The church is full of bits of stone found in and around it.

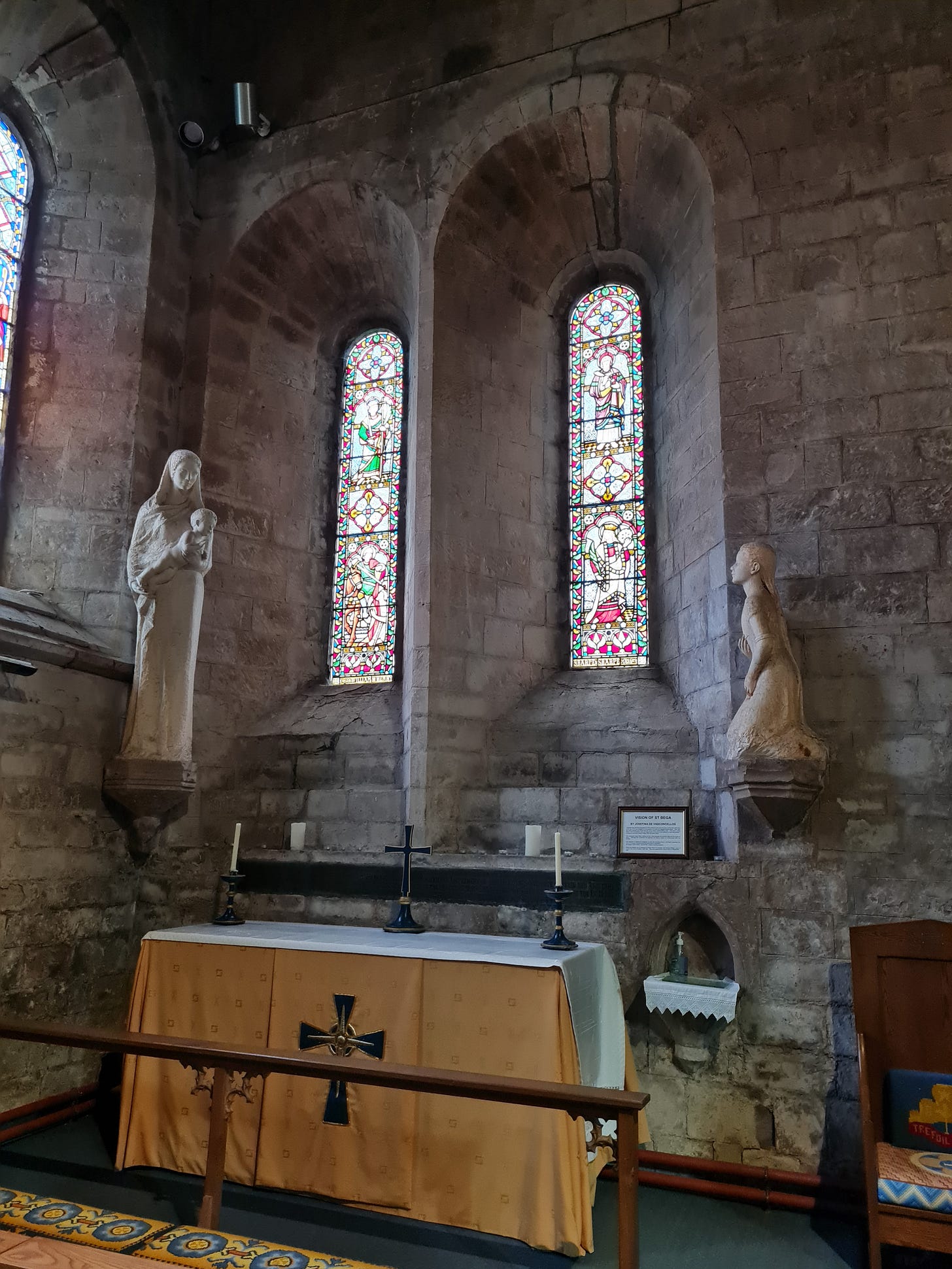

Most of the medieval structure has disappeared, due to the shortening of the chancel and demolition of some parts but a small chapel still exists on the north side, its altar in the position of its medieval forebear, next to a 13th/14th century piscina. The sculptures relate the story of the vision of St Bega, when she saw Our Lady.

The 19th century chancel.

Going back outside, another remnant of a 10th or 11th century cross stands outside, on the north side of the church. The land here is much higher than the church and so it seems likely some priory buildings lie here.

On the right here is a window from the chapel containing the St Bega sculpture. On the left is the beginning of the 13th century chancel, with several long lancet windows in Early English style.

The monks would have sat in their choir stalls behind these windows, which must have given a huge amount of light. After the dissolution and the demolition of part of the church, the old chancel was made into a schoolroom and library, precisely because of these windows. It still survives though separated from its nave and purpose.

Here is the priory from a distance. On the south side of the church, you can see here the original enclosure wall of the priory, still standing. The space between it and the church would have been filled with the priory buildings - cloister, dormitory, chapter house, etc. Quite remarkable that so much of the enclosure wall has survived.

Have you seen my publication - my translation of Shepherd’s Prayer by St Aelred of Rievaulx? Available now via Amazon around the world, the isbn is: 979-8344184814.