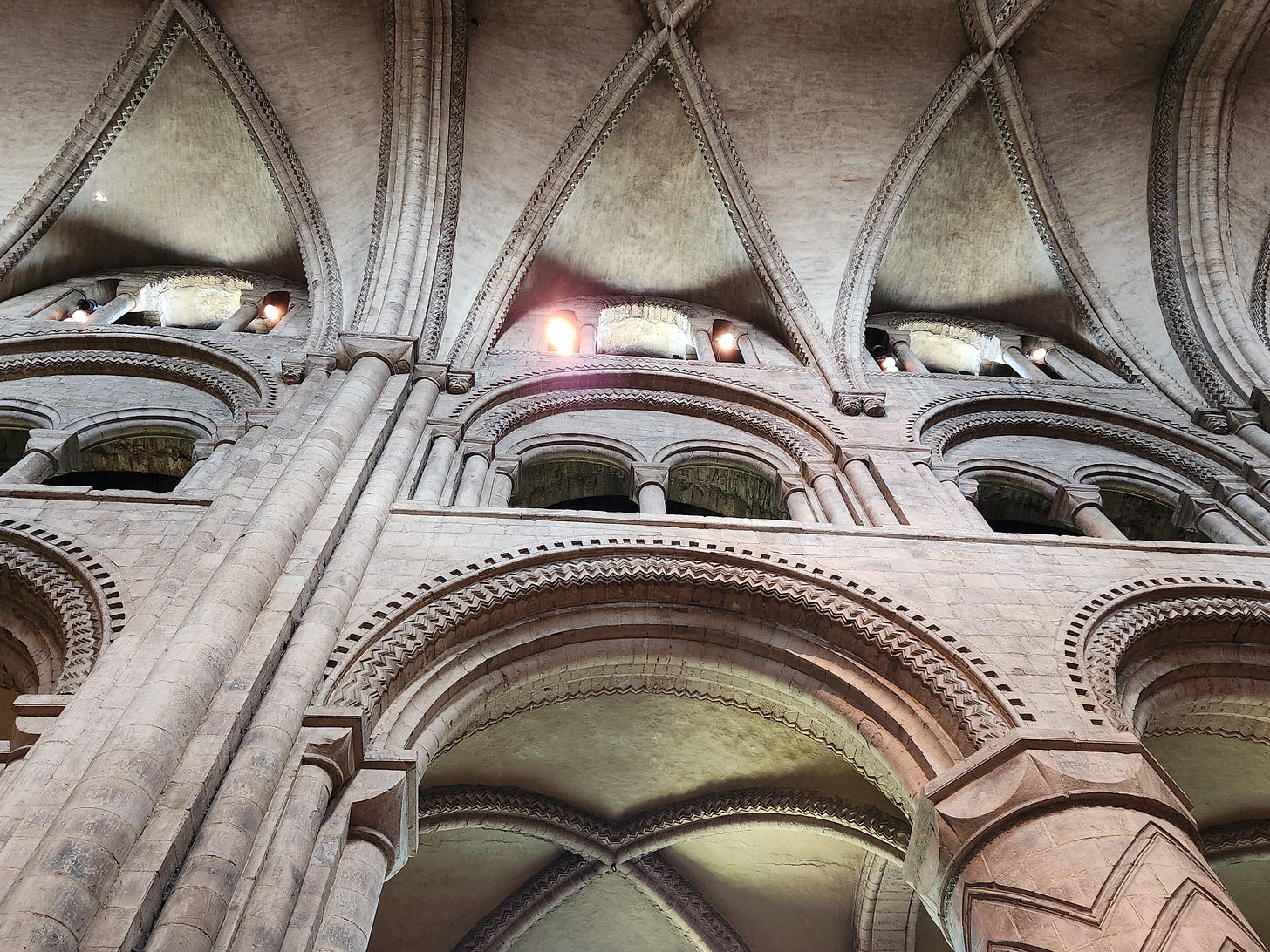

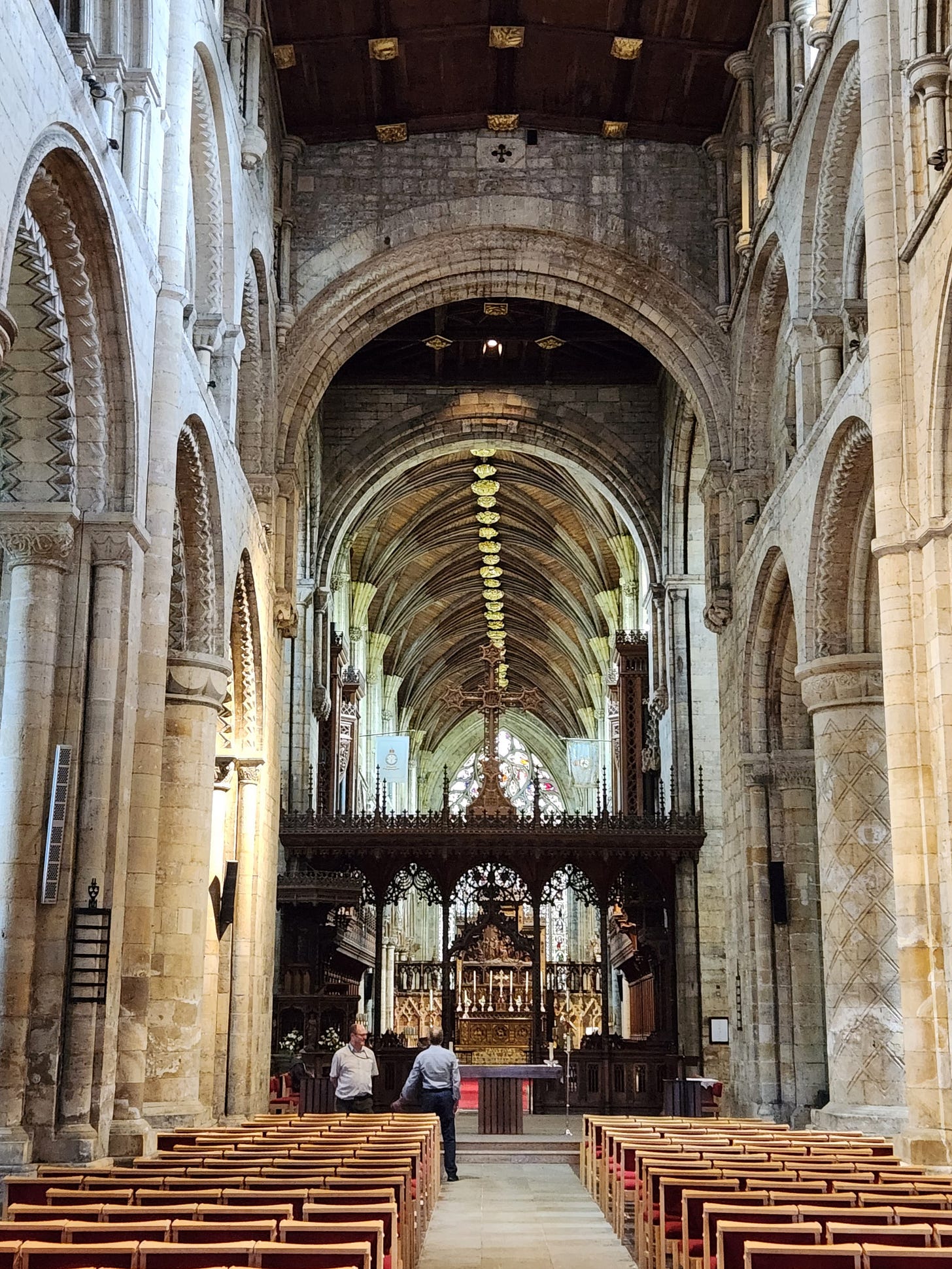

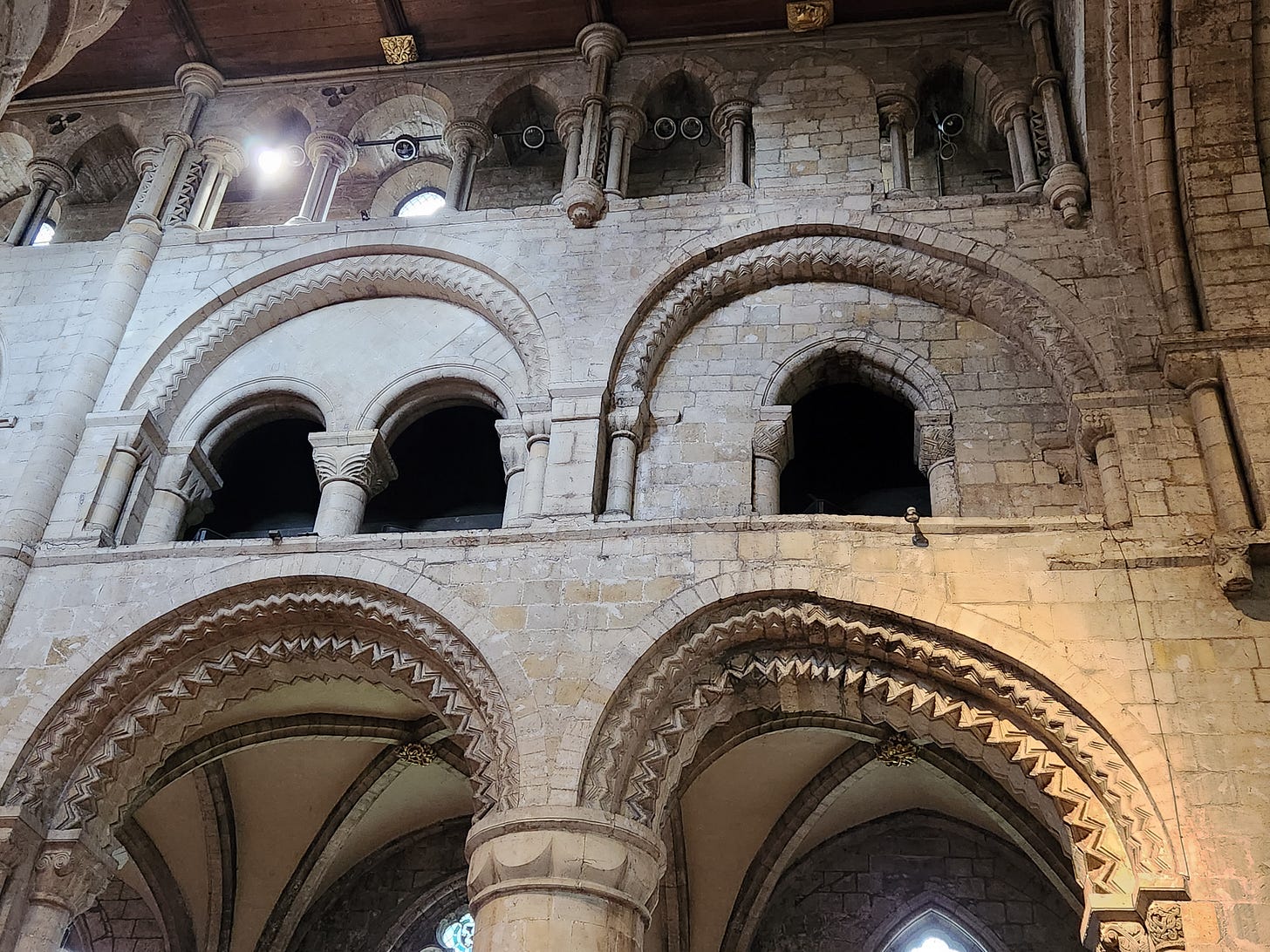

This is probably one of the most famous views of a Norman nave anywhere – it’s at Durham Cathedral (north-east England). Begun in 1093 and completed in 1133, it is overwhelming in its scale. The place was very busy when I visited but somehow I managed to get a photo with very few people in it so you can’t really see the enormity of those columns. They are 7 feet in diameter and 27 feet high – monsters in every way.

Durham is a rarity in that much of the Norman architecture survives – the arches in the nave and the chancel, as you see here, with their zigzag decoration.

This cathedral set a trend for the zigzag and also for the carving of the columns; you can actually see its influence at Selby Abbey (West Yorksire); though it is on a smaller scale, you can see similar designs, even to the extent that both Durham and Selby have full galleries on the upper side of the aisles.

The carving of the columns and their purpose is one of those mysteries – why did they do it and what did it look like painted? I’ve read various theories. One which seems to me to hold good is that some pillars were made in a particular way to be identifiable to pilgrims as a shrine to a particular saint. In a society where most people could not read, this makes sense. Think of the cockle shell of St James of Compostela, for example, which wends its way along the Camino. So some could have been to mark particular places, others perhaps purely decoration. Anyway, these kinds of pillars became popular, here’s the base of one at Lindisfarne Priory.

How were they carved? In the crypt at York Minster they have a bunch of Norman remnants stored in various states of undress. If you look at them closely, what you realise is that these pillars are made up of individual stones which are carved in one or two set ways, then fitted together like a jigsaw. It’s simple when you look at it.

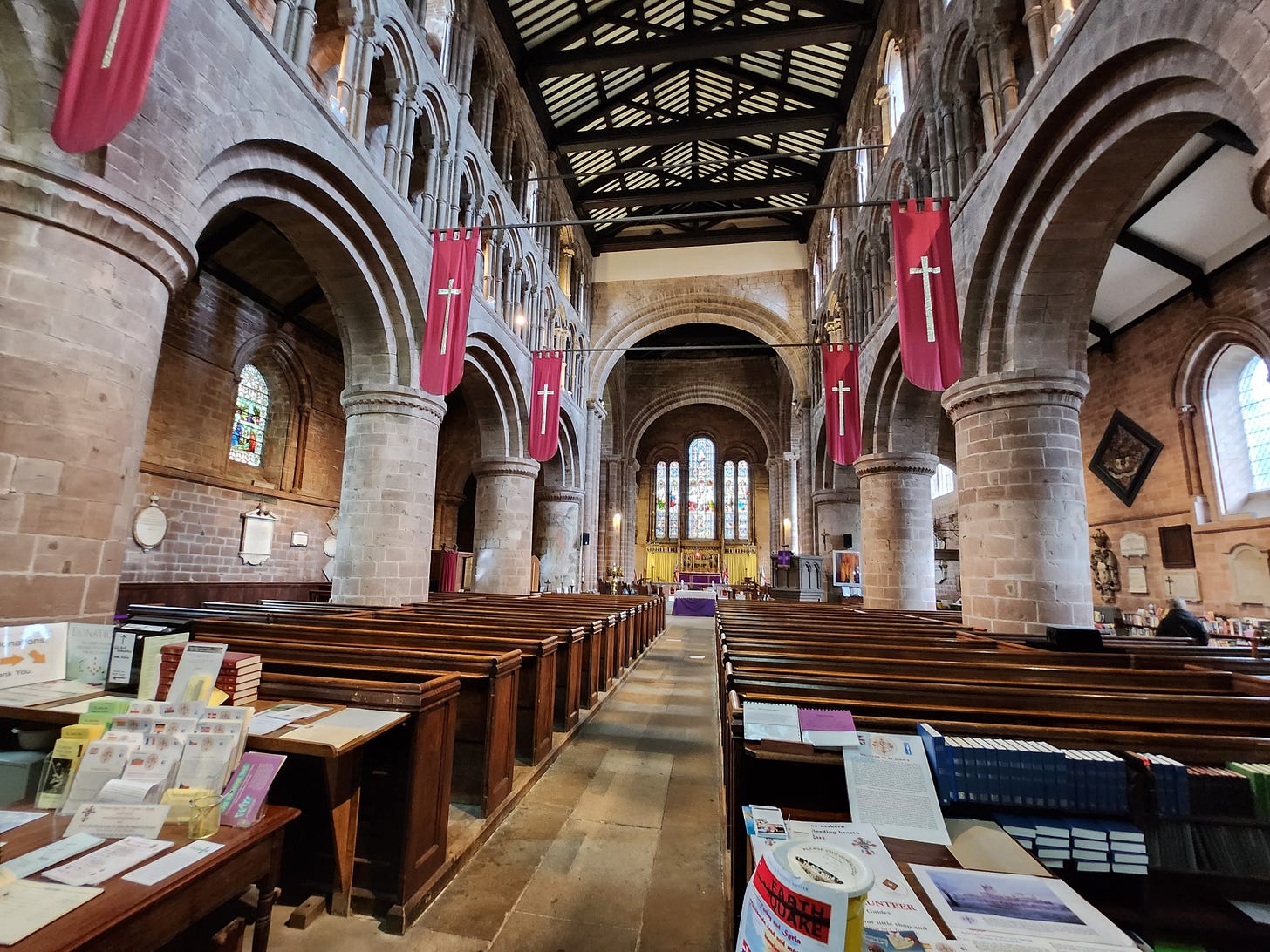

Other churches had plain columns which would have been painted. St John the Baptist in Chester has much shorter columns, with a small triforium (walkway) over the aisles.

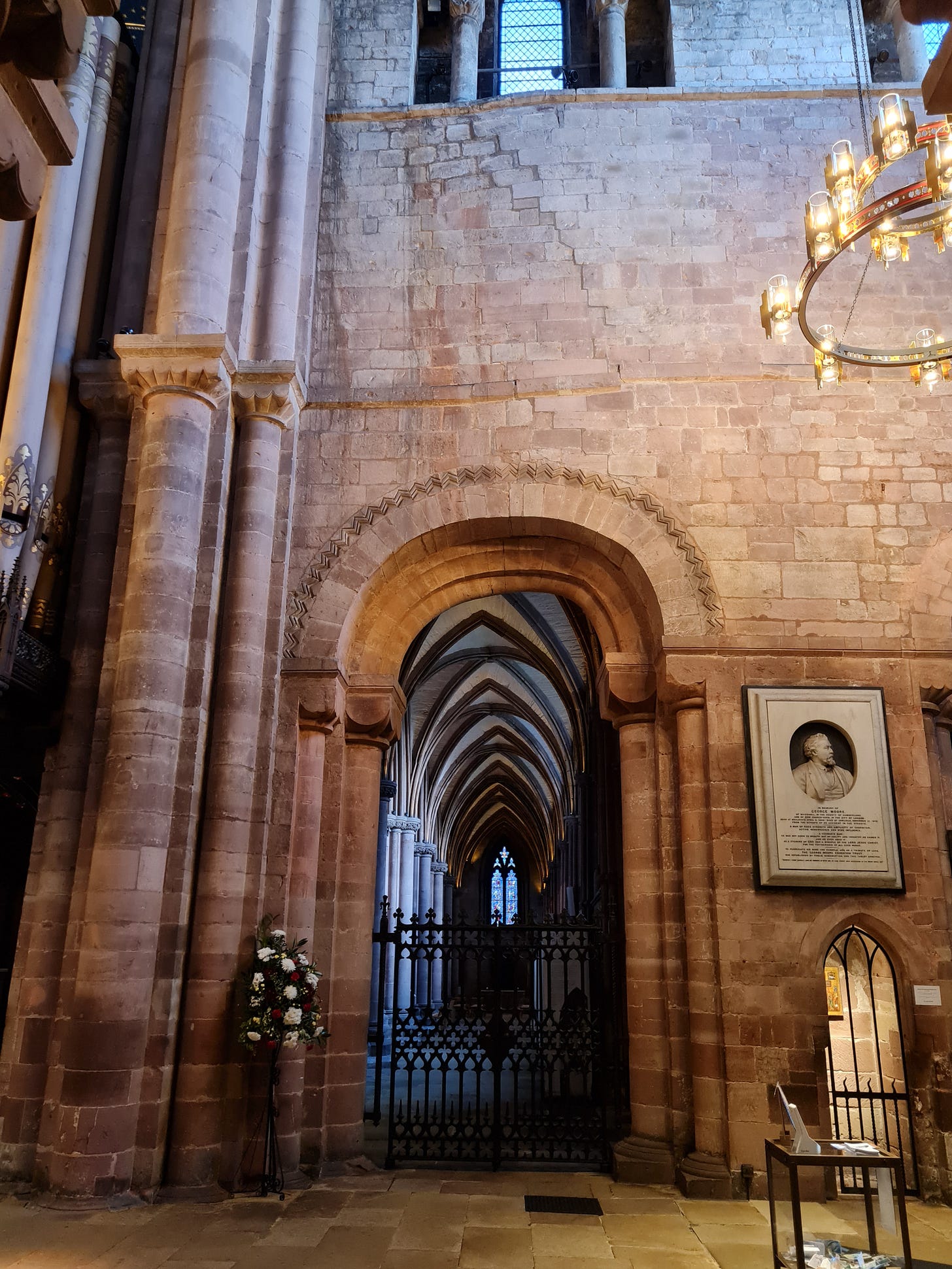

The architecture is huge, heavy and looks very solid. However, while I am not an engineer, what I have learned is that this kind of round arch doesn’t distribute the weight of the masonry above very well. Over time, arches can flatten and if the building is not on very solid ground, worse things can occur. Here’s a rather wobbly arch at Carlisle (north west England).

Sometimes these things occurred as the building went on or shortly after. Hurried repairs were made. Here’s the famous disaster at Selby, immortalised in some rather wonky stone.

Doorways were particularly important and Norman doorways were certainly impressive. Here’s Selby’s west door, though this is a late example of the work. It’s huge.

Most doorways and frontages were reworked over time so a pristine Norman front is very rare. We perhaps get an idea of what they may have looked like from the front at Lindisfarne Priory, which was of course, built by the monks of Durham. This photo is actually taken from the inside, but you can see a decorated door, with a walkway/portico above for the monks to keep an eye on things, and either side was a little turret kind of structure.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Incola ego sum in terra to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.