Welcome to new subscribers. In these Wednesday posts for paid subscribers, I take you on tours of some of my favourite churches.

When you go church crawling, you often find a plethora of similar churches in a small area. It becomes a bit boring - another Norman church/font/doorway, sigh. Crazy, really, when you’re looking at amazing survivals of 100 years old architecture!

In a big city with a huge and famous church the problem is worse - what would be a stupendous church in a small town becomes a footnote to its more famous cousin nearby.

A portrait from a piece of reset medieval glass in All Saints North Street

All Saints North Street in York is such a church, never full of visitors though it should be. It’s undoubtedly one of my favourites and I have visited it twice. All Saints is within the sound of York Minster bells but across the river, right next to the river in fact. Externally it looks like a fairly standard 15th century Perpendicular church with a nice spire.

Inside it is a true treasure trove of stained glass. It profited from its proximity to York Minster, with some of its glass undoubtedly worked by the same hands.

While much of the building is 15th century, there are lots of earlier periods represented, including the 14th century, where these east windows belong (Decorated Gothic).

If you stand right at the west end, this is what you see.

These pillars are a bit mix and match, dating from the 13th century onwards, but what you can see is a fairly narrow nave (probably similar in size to its Anglo-Saxon predecessor), with wide aisles on the north and south sides of the church, added in the 12th century but rebuilt multiple times after that. The simple screen you see in the middle here is 20th century but may be in the original place of the chancel screen. Much of the east roof is original, as we will see.

There’s so much to look at here that I’m going to split it into two posts. Today we will look at the south side and begin in the corner behind me in this picture - the west end.

The hole in the wall here communicates with an anchorite’s dwelling, which has been roughly rebuilt outside, as you can see through the window. This small window would have allowed the anchorite to observe Mass and the altar. Another hole lower down is hidden by panelling, and this one would have allowed her to receive communion.

I have written a little more about anchorites here, but there was a number of them in the area and the grave of a presumed anchorite woman was recently discovered in York. Most of those recorded in York were indeed women and were held in high esteem; Emma Rawghton, who was an anchorite at All Saints North Street, had political influence as a result of her perceived piety.

When I first visited this church, some of the windows were away being restored so it was a delight to go back and see them in their glory.

The east window in the south aisle is nice but unfortunately much restored in the 19th century so while the main design is from 1350, not all the glass is. Some of it has clearly been recycled, presumably after iconoclastic damage.

We can see the crucifixion in the centre, with Our Lady on the left and St John on the right, in the traditional positions. In the bottom centre is Jesus in the Garden of Gethsemane and either side of him are two women, who were most likely the donors of the window. This window would have been above an altar in the chapel, which is why the crucifixion is here.

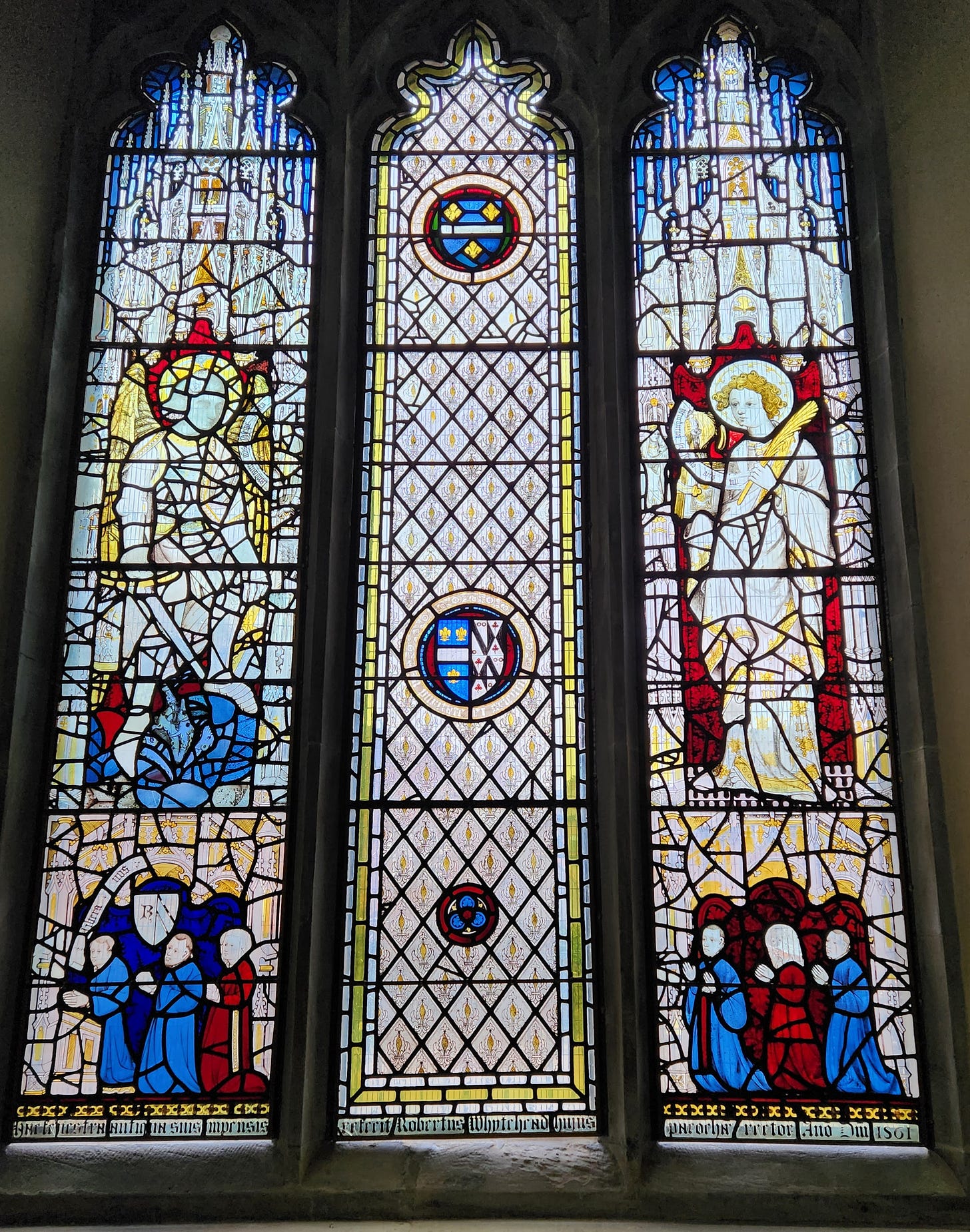

The next window is from 1430 and is rather faded in places due to the sunlight.

On the left is St Michael, with his sword. His face was stolen in 1842 and replaced with a shadowy replica. On the right is St John the Evangelist. Below are the donors of the window, asking for prayers of those who see it.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Incola ego sum in terra to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.